Claye Bowler - Yorkshire Sculpture Park residency

Claye Bowler's residency at Yorkshire Sculpture Park explored our concept of land ownership and the traces people leave on landscapes. During his residency, Bowler examined how individuals, through subtle acts like carving into trees or simply choosing where to rest, leave their mark and assert a sense of belonging. His work captures these interactions, creating an archive of personal histories and challenging conventional notions of who has the right to claim space. This exploration also touched on broader themes of social inclusion, historical legacies, and the unspoken rules that govern our use of public land, inviting us to reconsider how we connect with and perceive the landscapes around us.

Claye spoke to ART researcher Emilie Flower about his time at YSP.

EF: Claye, could you explain to me what you're doing here?

CB: “When I first came and started the residency there were a lot of race riots in the UK and people feeling like they owned the land that everyone lives on, and so I was thinking about that, and how that fell into things and ongoing land grabs of Palestine. I was trying to bring all of that together into something. I was thinking about the land at the sculpture park specifically, and how people feel they have ownership over that land, and how they reclaim and take that land, and whether that's a good thing or not.

And so I've been looking at a lot of the ways that people change the landscape. So if they are drawing by carving into the trees, or if they're just walking on paths and creating desire line paths, or how the sculptures change from people touching them... There's the remnants of people's experiences within the landscape, and how that makes the land an archive of that experience and memory, and if that results in ownership or not, whether people feel like it results in ownership or not.

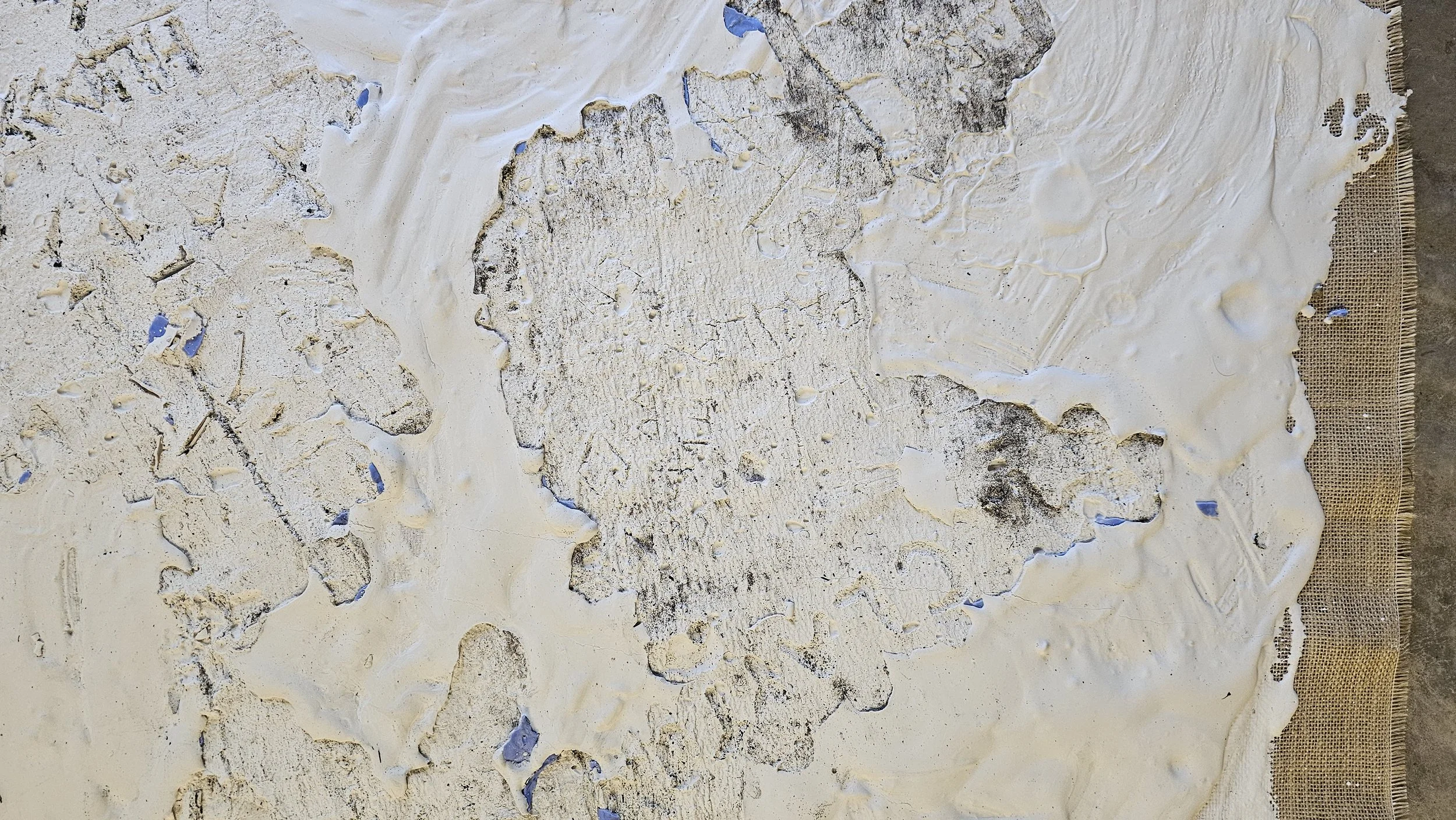

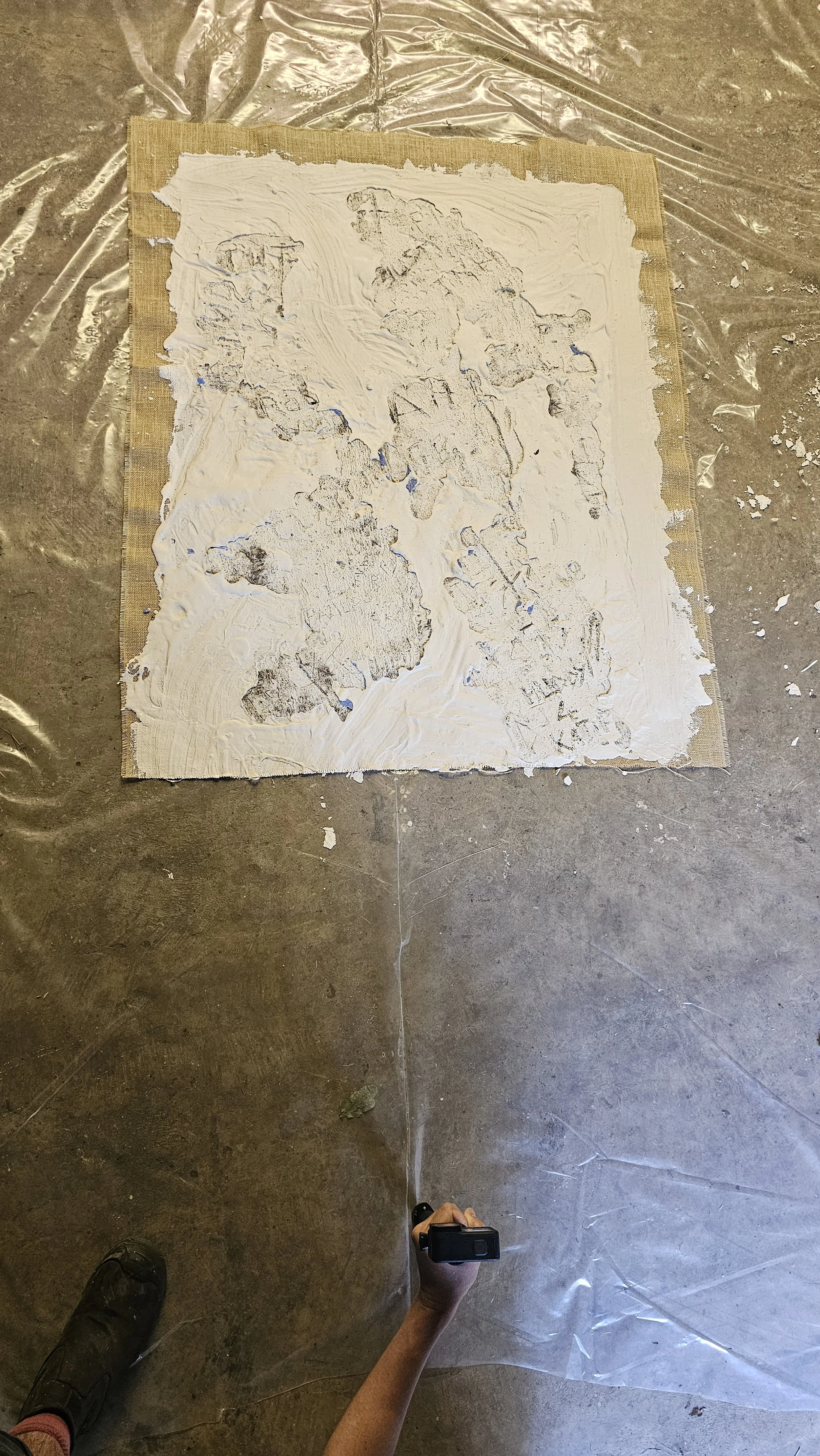

I’ve been trying to collect that or those kinds of experiences, specifically, how people have drawn into the trees. So I've made a lot of silicone casts of different things that people have carved, and some of them are people's names. A lot of the places are people's names. But there's also, quite silly things. So someone's just drawn a penis on a tree. But then also there's a bird. And then there's ‘Gay crew’. I really like that idea. I can imagine that gay crew, but I could be making a completely wrong assumption about that. I also have daddy, and I like that daddy is quite, like, roughly drawn, and the tree has grown around it. I like that that could just be a man that has children, but it could also be a gay daddy. You never know.

I think we don't take enough of people's likes, maybe they don't like it here, maybe this is an anti-ownership of the YSP, or it's an evaluation of the YSP, but people don't feel like they can actually tell someone that, so they've written it in a tree. So, yeah, I've been turning these into plaster casts so that we have what is actually on the tree. And then gay crew is immortalized in these, like, tableaus or tablets. All the stuff of those people deciding what they like. It's like we've got the Walk Of Art, that other people pay to have recognised. It’s the underground alternative way of marking the landscape, and so it's nice to immortalise them as important as the people who can afford to get their names on a Walk Of Art.”

Do you think that they do have some form of ownership of the land. And is it different because of this memory and this tracing, or leaving a different form, or is it just a different way of expressing it?

“I think it's a different way of expressing it. I don't know if it's a conscious way of saying that they own the land, but there was one tree that had the same signature in it six times, and it had a date, and it was over like 40 years that they came back to that same tree… And that one definitely feels like a pilgrimage, almost. It's like coming back to the same place and being like, ‘Okay, this is now. I'm back here again’. And they felt an anniversary of that space and time, like, ‘I own that tree’ almost. And in the same way that they're like, ‘it's not great to carve in. It's not good for their growth, and it does damage them, and stops them from stunting that growth from getting bigger. But I’m going to do it’. So, he has taken ownership just by carving. ‘RS’.

It's deciding to make that permanent change in that landscape as well, which is interesting. And all or most of these writings are the furthest you can get from the entrance. So people go far away into the park, and to a more quiet area that they decide is theirs. It's like, ‘I'm lost. If I write this here, they'll find me when I'm dead’, or something. But yeah, there's lots of different [things]. I like that. There can be so many different stories, and I can come up with some stories, and they might not be the stories, or they might. I might have accidentally got exactly what the story is. But I think that's what I like about doing that in my work in general, it's kind of collecting the unknown, and it's an ambiguous thing that is there.”

Is there a reason why you leave it ambiguous?

“I think I'm interested in the people that aren't collected, in terms of, institutionally and in museums, but also who is collected just in general and how people's lives are remembered. So families will collect heirlooms or information. I'm interested in this kind of space where you're not in any collection, no one's looking at you or collecting you. And I quite like the idea that some of these place things and people are being picked up, and whether those people are queer people, or if they're just people. I think I’m maybe putting a queer lens onto that. There's lots of ‘so-and-so loves so-and-so’ on the trees, and there’s the initials a lot of the time. And so it's that thing of, like, I could say all of those are queer people. And like, say that this is a queer archive of love. I like the idea that I can add that into the canon of collection, because that's what's not in the family collections. So it's taking ambiguous things and reading them in a way that adds them to the canon.”

How do you think links to what you're doing here, and does this work link to human rights?

“I think it was interesting to try and come up with because I think I work a lot within human rights amoust trans, queer and disabled peoples, and I was thinking about all the work they currently make, and how to link that to the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. I felt like I could make that work, but what's the point in me being in this space?

So I’ve been looking at this work, how people carve into rocks and what people leave behind in spaces that aren't necessarily the spaces to leave stuff, trees and rocks and things. So that was already on my mind, but I think it was trying to come up with something, and it does feel relevant to ownership of land and the right to own land, and who owns land and who doesn't? Like it's rich people that own it and mostly own it as a repercussion of slavery. When they abolished slavery, they were like, well, we'll give you this land as compensation, and for the fact that you had to give up your slaves. And now that land is still owned by these legacies. And so it's this very complicated space of like, now we're trying to take back that ownership of the land and having the right to walk on the land and live on the land and so there's lots of ideas there, but, but still taking out these wider ideas of land and, especially in Britain, with, who owns this land? Is it British people? Who are British people? What does that mean? And so there are lots of ideas that are tangentially about human rights.”

Yes, you’re talking about land rights. Is it a new territory for you in some ways, compared to queer or disabled rights which are more civic rights?

“Yeah, when you start talking about land rights, you get into different murky territory, but I had been thinking about queerness and the land. I used to run a residency program in my house near Huddersfield, and it was on the Moors, in a very rural space. I created that space to have queer people come back into the land. There’s a lot of times where queer people moved to the cities and into a safer space and away from small towns where it's not as accessible for them. And I've taken people on walks in the Moors, queer people and also people of colour, and there's been this, this kind of like, ‘I'm in the middle of nowhere and anyone can attack me right now’. There's instances where lots of people have felt really uncomfortable in that space. So there is something still relevant to this kind of queerness that we don't own that land, and we are pushed out with that land, and so it's trying to come back and take that space back. So there is definitely a queerness here. With the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, it's open to all, but it's predominantly white, middle class families who are here. And so it's like, are these the people that are the people who should be taking this land? And how do we invite more people to take ownership of this? There's a work I made where I was sleeping on one of the Henry Moore sculptures, and there's signs up saying, ‘Don't touch the Henry Moore's’. But there's kids on that sculpture all day, every day. And so no one's following that rule.”

Can you tell us more about the sleeping on the stone piece?

“[I] was trying to think about people on these sculptures who shouldn't be. But also I'm thinking about being, just, tired in general. I'm disabled and I'm chronically ill, and I'm in pain a lot, and need to just sit down and rest. And I was thinking about how there's not necessarily that space for that, but there's all these sculptures around and people are sitting on them. And I was trying to think, ‘Oh, maybe I can sit on them and rest on them. Like this very extravagant bench that is the Henry Moore sculptures that you're not supposed to be on, but that I've decided to take that space and use it as a rest space.”

It's another form of reclaim, isn't it?

“Yeah, but then I'm in a privileged position that I can do that. I've worked with the Henry Moore Foundation and have a relationship that's allowed me to be like, ‘Oh, can I actually just sleep on this?’ And they're like, ‘Yeah, come on, you can do that’, whereas other people can't do that. And so there's rules and things that some people think are fine and can do, whereas other people can't do the same thing, and then they're pulled up on them. So it's doing it, but also questioning it at the same time.”

And, who can do what on the land is, as you were saying before, about how people can do quite a lot on the land if they own it, but then your entitlement to it is ancient. That rule seems rather arbitrary.

[The residency] has started lots of thoughts, because I'm currently working on a big project for a solo exhibition, and I wanted this to be a different thing. I don't want to get kind of stuck in one idea, so this has been really nice to start alone in other ideas that can be taken into different ways. And, looking at land in different places.

I was also thinking about making a map of every bench in the sculpture park. So we have the normal map here, and it's got a list of all the sculptures. But I wanted to then re edit this map to add every bench and everywhere to sit down, like, can you sit on the plinth of the sculpture? Can you sit on the sculpture? And like, where's a good place to have a nap. What's like, where's goose poo? Is it good for a nap off the floor? I wanted to kind of create this alternative map that's accessing, it's not just about the step-free access. It's the access of, where's it's loud or where is there a cow that might walk on you if you're asleep. So it's thinking about all the different aspects. I think that'll be really interesting in lots of other contexts, because I went to Edinburgh Fringe this year, and I was like, ‘Okay, where can I nap during the day in Edinburgh city centre’? I was like, ‘okay, so we got that park. We got this other park’. But there's always a person on the corner playing bagpipes. So that's not a good place to nap. I think it's just something that I'm trying to think of, like mapping of the country in a way that it's all the spaces. Trying to find the accessible space to just live in, to just exist.

Sleeping in public in general is a big topic I've been looking at, like, where can you sleep in public? Can you sleep at the sculpture park in public? Because there's these social rules of where you can sleep. You can sleep on the train but not a bus. If it's sunny you can sleep, on the beach you can always have a sleep, but in the park, you can only sleep if it's sunny. So that's something I wanted to look at whilst I'm here, like, how resting at this sculpture park exists.