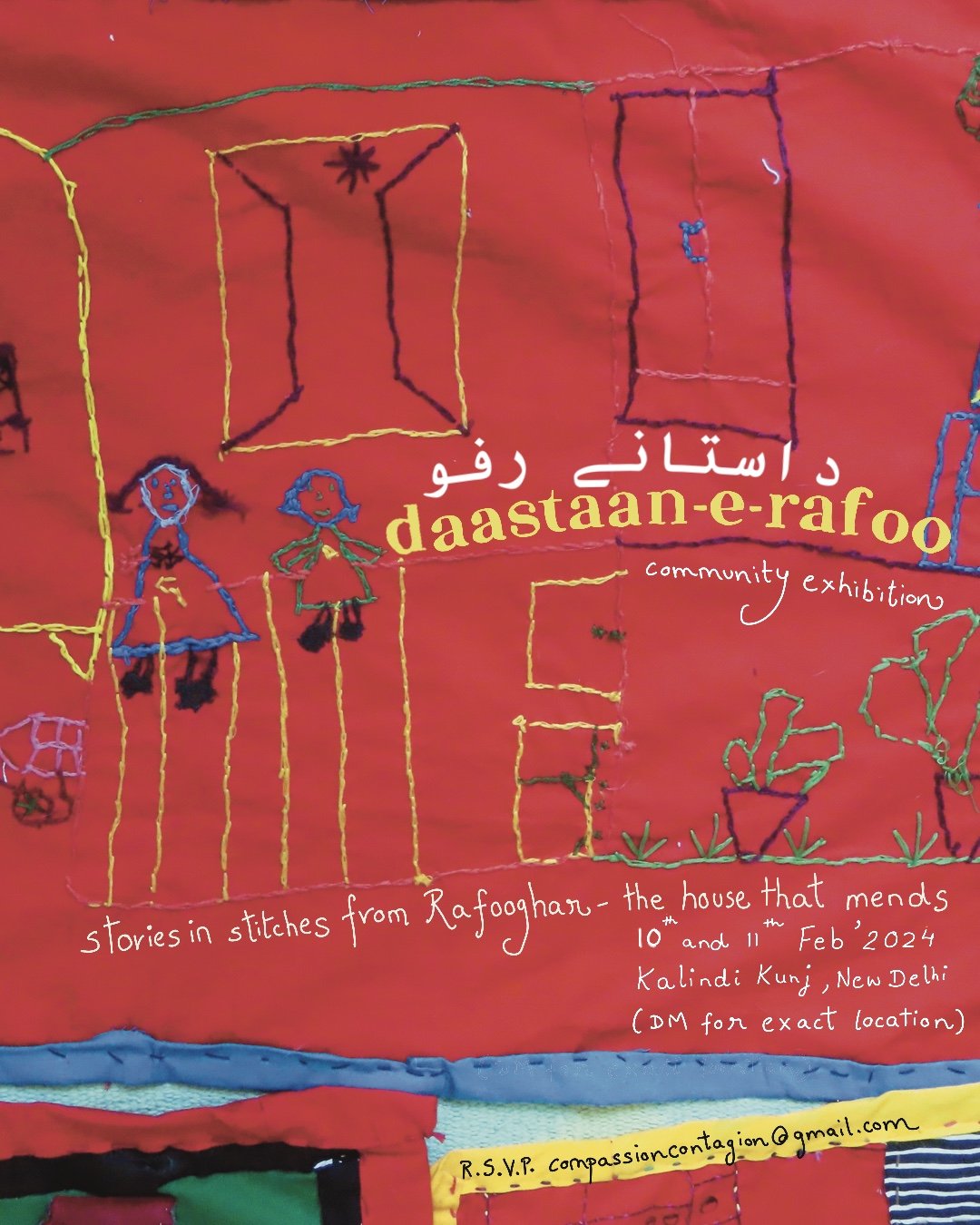

Rafooghar - the house that mends رفو گھر

Women face discrimination and social exclusion and are marginalised on the basis of their caste, class, religion and gender. Rafooghar aimed to be a safe and creative space where women could gather, share their stories, release their emotions, repair their emotional wounds, restore their broken selves and resist the erasure of their identities through the tools of mending, stitching, embroidery, and rights-based textiles. Just like a mender (Rafoogar) is not just an artisan who has the skill to repair damaged or torn clothes but is also a healer who breathes new life into them.

Rafooghar (inspired by the word Rafoogar/ Rafu Gar, needle-worker, darner or a cloth mender, رفو گر) by Compassion Contagion was commissioned in India as part of the Covid Legacies strand of ART. Rafooghar invited women from diverse backgrounds who often face social and cultural barriers that restrict their mobility, participation in public life, and access to education and healthcare, to join a series of arts-based workshops over six months to help strengthen vital social and emotional connections. These workshops aimed to address participants' concerns and fears, while also facilitating conversations on identity, rights, and their concepts of justice within the context of their identity. The stitching and embroidery activities were guided by templates that encouraged both personal and collective reflection, becoming mediums of therapeutic and creative expression, as well as powerful tools of empowerment, advocacy and social change.

From the very beginning, the women who attended shared that they lacked both time and space for 'fursat' (leisure) and 'sukoon' (peace). Others said they wanted to develop more confidence to express themselves and build community through conversation. These confessions helped shape what Rafooghar would become over the following months. Through drawing, mark making, embroidery, stitching and more arts-based activities, guided by conversation and reflection, the Rafooghar women connected emotionally and physically to themselves, each other and their communities. Through their artwork, they represented what they saw in their everyday environments as well as what they envisaged when they imagined alternative environments: as well as mapping their homes, their daily routines, the spaces they could freely navigate and those they were inexplicably barred from accessing, they emphasised their longing for green spaces and parks, despite their absence in their neighbourhoods, and their desires to move freely, feel peaceful, and to have a voice in their local communities.